Journey to Dundaga (2013)

By System Admin on Sunday, November 22 2020, 19:19 - New material - Permalink

[Originally posted in January 2014]

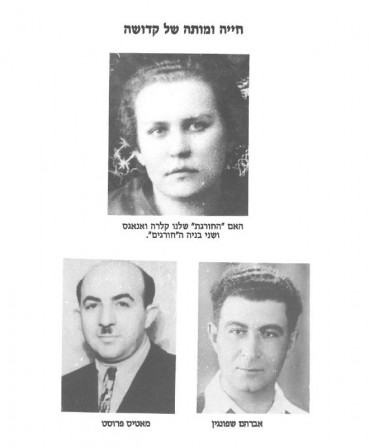

Last year, I had read the book published in Hebrew as אכן כך זה היה! "So it was indeed!", which is the life story of a man named Avraham Shpungin. Shpungin is one of only a handful of Latvian Jews who lived out all of WWII in Latvia. There were over 100,000 Jews in Latvia on the eve of the war and some 70% of them were killed during the Nazi occupation during 1941-1944. Almost all who survived were those who managed to flee east into the Soviet interior before the Germans arrived. Not surprisingly, Shpungin's story contains more than few incredibly lucky turns of fate. But the most remarkable of all of these took place in Dundaga, almost 70 years ago.

While the scale of The Holocaust in Latvia was small in comparison to other Eastern European countries, it has more of a personal meaning to me because it's the one Eastern European country I have visited and know personally. We have already visited many of the more well known Holocaust memorials in Latvia and I try to search out a few more with each visit. There are more of them being erected in recent years. I am also gradually reading more of the literature on the Holocaust in Latvia. Because Latvia is relatively small, there is some chance one might some day have a good understanding of the fate of most of the communities in the country and be able to visit most of the sites personally, to a degree that would probably be impossible in say, Poland.

But perhaps my reasons are even more selfish than that. Shpungin eventually moved to Rehovot, the town I grew up in, and it seems that is where he completed his book. In fact, he lived there during all the years I did when I was a kid. While I had always been interested in the Holocaust, I knew nothing about Latvia then. I didn't come to read the book until nearly 20 years after it was published, nearly 20 years after I no longer lived in Rehovot. But the more time passed since reading the book, the more the story sunk in, the more I studied maps of the area, and the more I had to know how much of the places described in the book still existed. I've spent a lot of time in the last 10 years searching for places in the Pine Barrens where nothing much ever happened at all, just because they'd been described by Henry Charlton Beck in Forgotten Towns of Southern New Jersey. Often there was very little left of them. But even just traces of iron slag in the sand or a cellar hole in the woods can be meaningful if you know what it once was. And it's all the more interesting because it's close to home.

And how unbelievable is what happened in Dundaga, even to someone who thought he knew a lot about The Holocaust! How many people in Latvia would read a book that had been published only in Hebrew and Yiddish? How many people in Israel who might read the book would ever go to Latvia?

On the drive from Riga to Kurzeme, I briefed the boys on the background to the story.

Shpungin was not from Kurzeme, but from the southeastern part of the country known as Selija or Selonia. Until WWI, Latvia was part of the Russian empire, and Selonia was the northernmost tip of the pale of settlement. He was probably born around 1920, just after Latvia first became an independent country. By the outbreak of WWII, like many Latvian Jews, he had moved to the capital city Riga.

As a result of the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, Latvia was annexed to the Soviet Union in 1940. But as part of operation Barbarossa, it was invaded by Nazi Germany the following year. Restrictions on Jewish clothing and freedom of movement, anti-Jewish propaganda, beatings, and synagogue burnings began almost immediately. By October 1941, Jews were confined to ghettos. By the end of the year, most had been shot in mass graves outside the cities.

The Riga ghetto was the largest in Latvia. It originally consisted of about 12 city blocks and had a population of about 30,000. After the mass killings of November and December 1941, it had been reduced to 2 blocks containing about 4000 able-bodied young men who were used as slave labor. Avraham Shpungin lived in this "small ghetto" for almost two years, assigned to various work-details throughout the city. During 1942, Jews from Germany and some other parts of the Reich began arriving in Riga by train. Some parts of the larger ghetto were reopened to accommodate them. They soon met the same fate as the Jews of Riga, either executed in the forests outside of town or forced to join the labor details. In 1943, the Germans began evacuating the ghetto for good, sending the remaining slave laborers to a series of concentration camps around the city. Shpungin was sent to the Kaiserwald camp on the north side of town.

The work details were the same, but while in the ghetto the prisoners had been allowed to return each night to houses they kept for themselves in what was still essentially an old residential neighborhood, they were now returned each night to barracks in a camp controlled by the SS and staffed by Polish kapos. However, he did not remain in Kaiserwald long. Soon he and about 200 other prisoners were sent by train to Dundaga. Dundaga today has neither a train station nor tracks, but at the time a narrow-gauge spur extended north from the town of Stende on the main Riga-Ventspils line. Kurzeme is sparsely populated even today and the Dundaga concentration camp was located some distance from the small town of Dundaga which probably had about 500 residents at the time.

Then as now, the most notable landmark in town is the medieval castle, which during the war was the German military headquarters for the region. It took us about two and half hours to reach Dundaga by car. We drove into town from the south, first encountering a few rows of typical Soviet-era concrete block apartment houses. The population of the town swelled to as much as 2000 during the cold war. Soon we saw a sign on the right for the castle, and I knew we were in the right place.

The castle is quite impressive. It was first built in the thirteenth century, but was obviously improved on during the intervening centuries. It is well maintained today. There is even a small museum, but it was closed for the season. A photo in a kiosk exhibit outside featured some old photos of the town, including a photo of the now-demolished train station. The main entrance to the inner courtyard was open so we went in and looked around. Outside there is a small park with some benches. It was actually quite warm for Latvia in December, but still too cold to sit down on a park bench. So we ate our lunch mostly standing up.

Shpungin describes the Dundaga camp as consisting of round tent-like structures made of cardboard and propped up by mud. The only amenity in the tents was a firepit in which wood could be burned for heat. The tents had small openings at the top, but the smoke would fill up the tent. The prisoners slept on the ground. Food was a bowl of watery horse-meat soup and a slice of bread per day. There was no washing or laundry. The camp was staffed by SS who were veterans of the Nazi concentration camp system. During the day, the prisoners were driven out into the countryside and made to clear the forest of trees. They also dug ditches, paved roads, and later constructed wooden barracks in some of the newly cleared areas. Prisoners who refused orders or tried to escape had cold water poured over them, were whipped bloody and left outside to freeze to death. While the prisoners performed work that was vital to the German war effort, conditions were such that life expectancy was not long. Shpungin describes this period as the worst time in his life. New prisoners arrived by train from Riga to replace the dead ones. The new arrivals were increasingly from western Europe, mostly Germany. All were young. Some were women.

The winter of 1943-44 was so cold and so many prisoners died of cold, hunger, and disease (mainly typhus), that burying them all in the frozen ground was a problem. So the prisoners were made to load their dead comrades onto trucks. They drove north about 20km to the Baltic coast. The prisoners had to carry the bodies out over the frozen sea-water and dump them into holes in the ice. So many prisoners died that winter that the trip had to be made twice a week. As the ice began to thaw, the bodies began to wash up on the coast, causing panic among the fishing villages. The Germans also worried some bodies might wash up in Sweden, less than 200km away. Again the prisoners were trucked up to the coast, this time to wade into the icy water and fish the bodies out, pile them on the beach, and burn them. Prisoners who froze to death carrying out this task were thrown onto the fires with the rest of the corpses. The living prisoners warmed their cold hands over the flames. In his typical biting humor, Shpungin writes: "...there burned together with the dead the belief in human civilization... the dead brothers with their flames warming the half-dead - who themselves wondered who would be next."

Another camp similar to Dundaga was set up at Popervale, about 20km to the southeast. Shpungin mentions a total of six camps in the area, including one for young Jewish women from Hungary who arrived in March 1944. They would sometimes be put to work clearing timber in the same areas, and these women told the men about Auschwitz. It was the first time Shpungin and his comrades had heard of gas chambers and crematoria, which were never used in Latvia.

By this time, the war was not going well for Germany. Although the prisoners were cut off from any source of news, they could perceive a change. Shpungin writes: "By the way the Latvians behaved towards us, we knew immediately what was really going on at the front". Occasionally, local farmers even offered them food. German propaganda told Latvians that the Jews were agents of the Soviet Union, which had annexed their country in 1940. Latvians tended to take this literally. Therefore they reasoned that if the Soviet Union was going to be victorious again, it was worth getting in good with its "agents."

As larger numbers of younger German soldiers began to arrive in the area, the purpose of the forest clearing and barracks building became clear. These were new recruits and their morale was not good. They were on their way to the eastern front and did not expect to live out the year any more than the Jewish prisoners did. More supplies began arriving in Dundaga by train. The Germans set up a TWL (Truppen-Wirtschafts-Lager "troop supply camp") in town. Kurzeme was being turned into a vast training ground for new armored and mechanized divisions that had to be ready to meet the Soviet army as the front moved westward. Shpungin suggests that Kurzeme was chosen for such a training ground not only because it was sparsely populated, but also because it was out of range of USAAC and RAF bombing, which was becoming a problem for German military installations by that time.

Shpungin was one of about 25 prisoners sent to work at the TWL, unloading train cars, loading trucks, and stocking warehouses. Their boss was an SS sergeant named Willy Wichmann. His access to desirable goods arriving from Western Europe gave him influence above his rank. He lived with some of the higher ranking officers in what had been the residence of the manager of the local dairy. Wichmann allowed the TWL prisoners to live in a makeshift apartment attached to one of the TWL warehouses. Apparently Wichmann was willing to give the prisoners more food and more freedom than his superiors would have liked, but he trusted that their increased productivity would make up for the risk of being found out. Sphungin suggests that Wichmann bribed the sadistic concentration camp commandant to look the other way. Shpungin describes this as the best conditions he lived in at any time during the war. The TWL prisoners were even able to sneak some extra bread back to their less fortunate brethren at the concentration camp, when they met them on occasion at the train station.

At one point, Wichmann even allowed the prisoners to carry away a glass jar of coffee grounds that had been crushed in transit. They meticulously cleaned out the glass shards and brewed the coffee, the first any of them had had in years. Unfortunately, an officer noticed the smell of fresh coffee coming from the prisoners' quarters and became irate, accusing Wichmann of letting the biggest enemies of the Reich live in luxury while our boys were dying at the front. Wichmann could not bribe his way out of that one and had to crack down on the prisoners' conditions to avoid a court-martial.

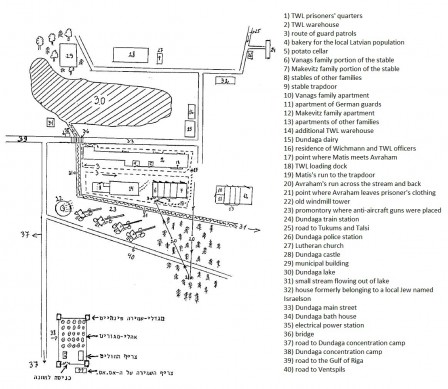

After lunch, I got out my copy of Shpungin's book and studied his diagram of the town as he remembered it after the war.

The lake actually surrounds the castle on three sides, but it was clear looking out from the castle entrance, that this was the part of the lake depicted in the diagram as (30). This is also clear due to the position of the Lutheran church (27) relative to the castle (28). This means that north is more or less the lower left corner of the diagram.

It is clear that with our backs to the castle entrance, we are looking at the bridge (36) and road (33). The large red brick building to the left is the dairy (15). It appears to still be in use as such. The white structure on its left was almost certainly Wichmann's quarters (16). The relative positions of the dairy and the bridge suggest that the long, boarded-up structure between them is the main TWL warehouse (2). Up until this moment, I didn't know if it hadn't been demolished many years ago, along with the train station. But the more I stare across the lake, the more sure I am that's what it is.

One of the prisoners at the TWL was a tailor named Matis Frost. He was from a tiny town in Selonia but had moved to Riga sometime before the war. Unlike the other TWL prisoners, Matis was made a valet to Wichmann and the TWL officers at their quarters. Given his job and his good relations with Wichmann, Matis was allowed the unheard of privilege of walking the 500 meters or so from the prisoners' quarters (1) to the officers' quarters (16) unguarded and wearing civilian clothing. One day in July 1944, Avraham saw Matis running down the street alone. They met at the point marked (17) in the diagram. Matis had just overheard a phone call at the officers' quarters. The Soviet army was advancing from the south, between Riga and Jelgava, less than 120km away. The TWL was being dismantled. All the Jews were to be returned immediately to the concentration camp, which itself was being evacuated. Kurzeme would soon be the front, and non-combatants would be evacuated to Germany.

Neither man believed they would live to see Germany or anywhere else if they returned to the camp. Mortality there was appalling even in the best of times, and with the TWL and the military training bases gone, the Jews would be nothing but a nuisance. Besides, earlier in the war they had grown accustomed to seeing mass executions follow promises of "evacuation". Behind them were stables (marked 6, 7, and 8 in the diagram) where the families of the local Latvian workers kept their livestock. The stables had a trapdoor (9) through which they shoveled out manure, to be used later as fertilizer. Matis, who was wearing civilian clothes, ran around back of the stables (19) and crawled through the manure into the trapdoor. Avraham was wearing the striped clothes of a prisoner, but had clothes that Matis had sewn for the other prisoners out of German tent cloth. He ran past the stables (20) across a small stream (31) and discarded his prisoner's uniform in the woods on the other side (21). He then ran back across the stream and into the trapdoor.

Soon after, the Germans assembled the TWL prisoners and realized two were missing. They used dogs to track the scent across the stream and into the woods. Several hours later they returned, apparently gave up the search, and turned to more pressing matters. Avraham and Matis hid in the attic and watched as the Germans burned or destroyed large quantities of supplies. The fires and explosions continued into the night. The two men planned to leave as soon as the coast was clear and try to make their way southeast towards the Soviet lines.

They were awoken the next morning by the sounds of engines, many of them, and loud. Their first thought was that the Russians must have arrived much quicker than expected. When they peered out through the slats, they saw tanks, artillery pieces, anti-aircraft guns, half-tracks, trucks, and soldiers, all of them German, all of them covered in dirt, as far as the eye could see in all directions. These were not the SS. These were combat soldiers, the remnants of units that had invaded the Soviet Union's northern territories three years earlier, that had laid siege to Leningrad, and had since held the Red Army back, one rearguard action at a time, until they'd been pushed back this far west. They were now trapped in Kurzeme in what became known as the Courland Pocket, some third of a million heavily armed men, more than the entire civilian population of Kurzeme.

The Soviet Army outnumbered the German army several times over, but casualty ratios were always heavily lopsided against the Soviets, even when the Germans were losing. Kurzeme had no strategic value to the Soviets, so rather than get entangled in what would be another painfully bloody battle, they bypassed Kurzeme and headed southwest, towards Koenigsberg and ultimately, Berlin.

Avraham and Matis couldn't have known half of this at the time. What they did know was thirst. After several days, they grew desperate. When the wife of the local blacksmith, Mrs. Makevitz, entered the stable to milk her cow, they spoke to her and asked for water. She left, and they knew that whoever entered next would determine their fate one way or another. The woman who entered was Klara Vanaga, the wife of a railroad worker, Anton Vanags, who lived in the nearby apartment house (10 in the diagram) where the Makevitz family also lived (12). Every morning for the next 10 months, either Klara or her 16-year-old daughter Skaidrite would bring them bread and milk, sometimes even coffee, hidden in the bottom of a bucket. Periodically, Anton would arrive to clean the stable and would tell them news from the front that he had heard on the railroad. The Vanags family was not well off, and German soldiers were billeted in the apartment next theirs (11). Klara and Anton had three children. The entire family would be killed if their actions became known. The only other person who knew of their secret was Matilda Makevitz.

The soldiers of the Courland Pocket were the last German soldiers of WWII to surrender, a full week after the fall of Berlin. Apparently, the Soviets had a hard time convincing them that news of Hitler's death and Germany's surrender were not just disinformation. And the Soviets remained slow to enter the pocket, wary of the vast numbers of able-bodied and heavily armed Germans. The rest of Latvia had been reabsorbed into the Soviet Union by late 1944, but Kurzeme remained a closed military zone for some time even after the surrender of the pocket. Avraham and Matis were thrown into an interment camp for suspicious individuals for a few weeks. When the Soviet authorities decided they were harmless, they were given written authorization which allowed them to return to Riga.

After orienting ourselves, we head away from the castle (28) in the direction of the church (27), which is clearly farther away than as shown in Shpungin's diagram. The white house in the center of the picture is almost certainly the house marked as (32). The street sign shows the street to the right to be named "Dinsberg Street".

We turn right onto Dinsberg Street. This is the apartment (16) adjacent to the dairy (15).

As we pass the dairy and continue on down Dinsberg Street, the main warehouse (2) looms into view. This is the part of the street Matis ran down after overhearing the phone call. The cross street on the other side of the yield sign is (33). Shpungin's diagram shows Dinsberg street continuing straight on through this intersection. It is not paved, but there is a footpath on the other side that crosses to the left of the warehouse.

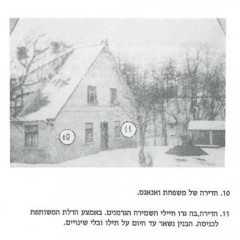

Beyond the warehouse (2) lie the stables (6-8). Sphungin's two annotated photos from the 1970s leave no doubt that what we are looking at is the same structure that he and Matis Frost hid in from July 1944 to May 1945.

|

|

They hid in the attic marked (6), which belonged to the Vanags family. His footnote states that the chimneys, wider doors, and new roof were added since the war, and the building was now being used to repair agricultural machinery. He refers to the hut in the foreground as "the guardhouse".

|

|

The warehouse marked (14) is no longer standing, but the truck ramp and part of the square window in its rear wall are still visible when we were there. It is possible that the more distant structure visible beyond it was the location of the prisoners' quarters (1).

Here is the same cluster of buildings viewed from the opposite direction on the other side of the creek, just up road (37) in Shpungin's diagram. The stone building on the right side with the two small round windows is the prisoners' quarters (1). Behind and to the right of it are the remaining front and back walls of what was building (14), and behind and to the right of that the stables with new red metal roof (6-8).

And just up road (37) are the remains of the windmill (22). During the siege of the Kurzeme (Courland) pocket, Shpungin says the Germans mounted search beams on it to aid their anti-aircraft guns (23). The road visible here is (40) in the diagram which Shpungin describes as the road to Ventspils. It does lead west, but it does not continue very far today.

This is approximately the spot where Matis meets Avraham (17). The structure partially visible on the right is the main warehouse (2).

The turn in the stream seen here is just off the area shown in Shpungin's diagram. The points where he crossed over and back (20) must have been somewhere on the left side of this picture, in the wooded area closer towards the stables.

After the war, Shpungin finished his studies at Latvia University and got married. He spent much of the 1950s attempting to locate the sites where his relatives and acquaintances had been murdered in Selonia. He and other survivors, most of whom had lived out the war years in Russia, attempted to erect monuments. In the 1960s, he began writing (in Yiddish) about his experiences. He attempted to publish his stories, but was told by editors of a Yiddish literary journal that they were "utterly disconnected from Soviet Communist reality" and "lacking in ideological elements and Marxist approach". He noticed that many of the monuments he had erected had been removed, or had all the Yiddish letters and stars of David filed off from the stones. In the 1970s, he moved with his family to Israel, settling in Rehovot, where he worked at the Weizmann Institute of Science. Matis Frost also moved to Israel and was living in Rishon LeZion at the time the book was published.

There are many new holocaust memorials in Latvia now. Some of them are very large and all feature stars of David. We found this small one about 5km up the road from Dundaga to the coast (37 in Shpungin's diagram). It is on the opposite side of the road from where Shpungin drew the camp (38). The inscription in Latvian reads "To the memory of 1200 murdered Latvian and European Jews of the Dundaga death camp in the years 1943-1944" and beneath that "The Council of Latvian Jewish Communities and Congregations". There is a small plaque in the lower left corner that appears to bear the symbol of the European Union. I hadn't noticed that at the time and it is too small for me to read from the picture.

Shpungin's book comprises 30 years of writings, which are not always datelined. The chapters appear to be ordered as he wrote them. Towards the end he writes:

“Throughout the long years that have passed since liberation, and especially now, when I’m slowly coming to draw up my life’s sum total, these years that have passed so quickly, I’ve frequently thought about this and asked myself - in a situation similar to hers, would I have done the same? And if I’m to be honest with myself and tell the truth, then with great shame, with a stooped head and downcast eyes I must confess, that I’m not at all sure if I’d be able to do and act, as Klara did and acted. The sense of shame summons to my heart the idea that this woman was indeed a saint, truly one of the 36 righteous ones of the world, all the more so as she was never repaid in this world for her deeds. Klara and her family, who gave me back my faith in humanity, the faith that not all are murderers, criminals, or indifferent spectators, continued on after the war in their difficult, workaday lives. My friend Matis and I were concerned with our own affairs, family, work, children, and could only infrequently come out to visit her in Dundaga. The local municipality did not give her any recognition or thanks, much less material support. Matis and I helped materially any way we could under the circumstances, but our opportunities under Soviet conditions were few and very limited.”

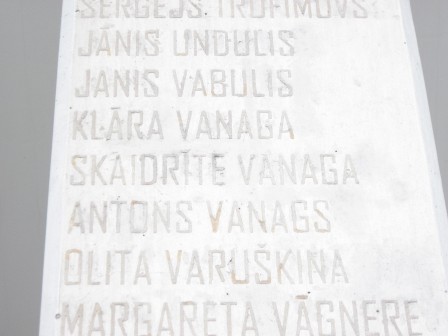

One of the most noticeable and centrally located holocaust memorials in Latvia is the ruins of the Choral Synagogue at the corner of Gogol street and Dzirnavu Street in Riga. This is one of the synagogues that was destroyed in the summer of 1941, together with the people inside it. In 2007, a new monument was built next to it commemorating Zanis Lipke and several hundred other Latvians who saved Jews during the war. It is supported by diagonal concrete columns into which the names are carved. The day after we returned from Kurzeme, I gave the boys the day off and went for a walk in Riga and visited it. It contains the names of Klara and Anton Vanags, and their daughter Skaidrite, who was the only one of their children old enough to understand what was going on during the war. Shpungin remained in touch with her at the time the book was published.

Klara Vanaga died in 1961 of brain cancer.