Three communities in twenty crates…

By System Admin on Sunday, November 22 2020, 17:07 - Sample chapters - Permalink

Towards the end of 1945, as life in Riga resumed its normal course to a certain extent and I began to work and became again an ordinary member of the public, I decided that I must go to the town of my birth, Jakobstadt, and see on the spot with my own eyes what had happened there during the war years. Of the eight hundred Jews who had lived there before the war, I found about ten families numbering about thirty or forty souls. These were those Jews who had immediately, during the first days of the war, left everything behind and fled Jakobstadt eastwards, into the Russian interior. Indeed, far more Jews had fled, but only a few were fortunate enough to have been running in the right direction and not fallen into the hands of the Germans who had penetrated in to Latvia quickly and caught them on the way. Only those who fled to the north-east made in through. All the others were stranded in areas that had already been conquered by the Germans and were stopped. These people were sent back to their towns that they had fled, or else were shot to death together with local Jews in the places they were caught. From the Jews who had returned from Russia and from Latvian neighbors who were friends of my family from before the war, I received precise information on the bitter end of the Jews of Jakobstadt and the surrounding communities.

Immediately following the entry of the Germans, or more precisely even before that, immediately after the Russians ran away so as not to be taken prisoner, in the final days of June 1941, the members of the Latvian organization “Aizsargi”[1] were already carrying out the first attacks on their Jewish neighbors. For the time being, there were no murders, they made do with just robbery and beatings. In the meantime, they sheared off the beards of orthodox Jews, desecrated the synagogues, abused the elderly, and looted from Jewish apartments whatever they wished. One week later, the Jews were banished from their apartments, they were put into the three study houses, and during the day they were led to various hard labors. This humiliation lasted only about ten days and by about July 20, 1941, they were led on foot under heavy guard by the local police and other active volunteers to Kūkas, about 12 to 14 kilometers from Jakobstadt (see also the map of Latvia and annotation in the preface). The sick, the elderly, small children, the blind and crippled were carried by horse and cart, all the rest walked on foot. They were told they would have to work hard, to dig peat in the bogs and to live in shacks that had previously been inhabited by the mine workers that had been brought from Poland and that had stood empty already since the beginning of the war. The Jews that had been brought there worked under close guard for about a week digging peat and then were made to broaden and deepen the pits that had been left since the removal of the peat back in the time before the war and thus to prepare graves for themselves. At that same time, remnants of the Jews from two nearby towns, Viesīte and Nereta, were also brought to the same place. These were small communities and many of their Jews had been killed by gunfire immediately after the entry of the Germans. Once the pits were ready, on July 31, 1941, late in the afternoon, the blue busses arrived containing Major Arājs’s Latvian shooter kommando (see the chapter “Our Murderers”). With the help of the local activists and volunteers, that very evening they lined up the men, the women, and the children by the pits and shot them to death. Not all of them died right away, but what the bullets didn’t do was completed by the grave itself, the earth, and the lime that was scattered over them. The farmers from Kūkas, who lived nearby to the killing pits, told me that after the shooting, all evening, until late at night, they could hear terrifying heart-rending cries, moans, and wailing. Later on, the voices grew weaker and in the morning the silence of death prevailed.

After such hard work – not in every town were there so many Jews – the shooters spent the night drinking liquor and singing songs not far from the pits of the killed. The next morning, they hurried off and left in their busses, according to a precise plan, to other towns, in order to execute additional Jews. Time was short, and all around there were still so many Jewish towns, so much work… The local volunteers who had helped the shooter kommando also partook in the nightly drinking with them. Early in the morning, they covered and straightened the pits thoroughly with dirt and quickly ran off, so as not to be late in snatching up better Jewish apartments and looting whatever housewares still remained, as well as other goodies. Among them were a number of students who had studied with me at the gymnasium in Jakobstadt. Sometimes we had studied together at my house. On such occasions, my mother would sit them at the table and serve them baked goods. Most of them later fled with the Germans and lived peaceful lives in Canada or Australia.

Once the shooters and their assistants had gone, some of the farmers from the area approached the three or four pits that were 10 to 12 meters long each that had just been covered with dirt. They later related that the uppermost layer of fresh dirt above the pits had cracked open as if after an earthquake. This occurred apparently due to the shaking and spasms of those buried who were still alive and had lain together with the corpses during their last moments of dying.

When I came to Kūkas in the spring of 1946 and the farmers showed me the pits, the graves were already covered with fresh green grass, a sign that life in the world goes on as is its fashion, and the earth covers and makes forgotten humanity’s greatest tragedies.

In meetings with Jews who had returned to Jakobstadt from Russia, and later also with those originally from Jakobstadt, Viesīte, and Nereta who returned after the war and settled in Riga, we decided to exhume the bones of our families and relatives from their grave in Kūkas and bring them to the old Jakobstadt cemetery for Jewish burial. In order to fulfill this undertaking we directed collective petitions to the administration of the city council and also to important institutions in Riga. However, at first, they didn’t even bother to honor us with a reply. But we didn’t despair and stubbornly continued writing petitions and requests, and only after negotiations with the bureaucracy that lasted some ten years, did we receive in the middle of the 1950s license to exhume the bones of the deceased from their graves. The conditions of the license stipulated that we perform the entire action at our own expense, and the city administration would give us only trucks for transporting the crates. During the years of the long negotiations, a number of other Jewish families arrived from our towns who had been exiled to Siberia some time before the war as anti-Soviet elements, meaning former Zionists, Bundists, or simply rich Jews. In this way, the number of Jews grew, and we managed to get everyone to donate until we possessed the necessary sum. We ordered immediately 20 large crates of unfinished wood from a carpentry shop, two meters long and 90 by 90 centimeters wide and high. However, it was a problem finding workers to dig and exhume the bones of the dead, because no one wanted to perform this depressing job. Finally, we found a group of Gypsies from the surrounding villages who agreed in exchange for a sum of money agreed to in advance to dig and exhume the bones of the dead and place them in the crates. The main reason that the Gypsies agreed to do the job was the hope that they would be able to get rich even from dead Jews, to strip them of gold chains, gold rings, and maybe find other valuable jewelry in the pockets of their partially rotted clothes. The conceptions of gold and Jews were still rooted in the thoughts of our neighbors, as expressed in the saying: “Where there are Jews, there is always gold.”

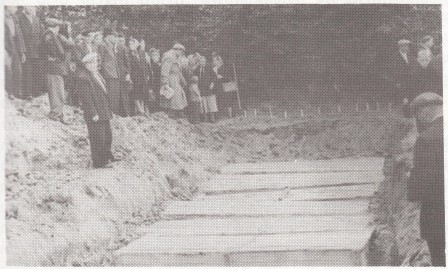

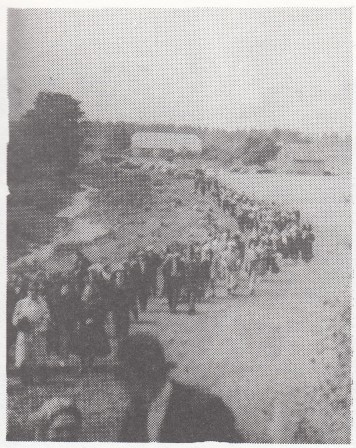

Under the supervision of individuals from among the elder inhabitants of the Jewish community of Jakobstadt, the workers dug and uncovered the pits, exhumed the rotted bodies, and placed them in the crates. Immediately after that, on a Sunday, Jews gathered from the area and also from Riga and other cities, to take part in the funeral. The cantor of Riga arrived too, representatives of the community in Riga, and many just plain Jews. The memorial was held by the open pits in Kūkas, in the presence of an audience of several hundred men and women and the crates filled with the bodies and bones of their brethren. Afterwards, in rented busses and in trucks belonging to the city, the procession and the dead were driven to the old Jakobstadt cemetery (see accompanying photos). One family, Rosenberg, also brought a crate of the bodies of their relatives, who had lived in a small village where all the Jews had been executed by gunfire close to the places of their residence. The Rosenbergs learned of the place where the murder had taken place, and they had dug and exhumed the bodies and brought them in a small crate to the cemetery for the common burial. On the crate was written the name of the deceased – the Rosezky family. On that same day, several crates of bodies of Jews who were murdered in the neighboring towns of Viesīte and Nereta were also brought to the cemetery. In these places, the communities had been small, and some of the Jewish inhabitants had been murdered there by local murderers immediately following the German conquest. One Jew, Berl (Boris) Vaserman who had previously lived in Viesīte and returned after the war from exile in Russia, arranged the exhumation of the bodies and their transportation in crates directly for burial in Jakobstadt. After the heavy crates had been lowered into the mass grave, the procession said kaddish and the cantor sang “God full of mercy”. Official representatives of the government and the city were not present and there were no eulogies or expressions of sympathy or condolences. After the grave had been covered with earth, most of the procession scattered, but I couldn’t leave the place. Something prevented me from leaving and held me here, among the broken, cast-aside, and moss-covered gravestones. I walked among them slowly and in my thoughts passed images from our town’s past that was in fact so far from me, but so close to my heart. I recalled the details of events from the days of my youth in Jakobstadt, my relations with people who were now buried here, under the old stones.

I found the grave of my (maternal) grandfather, Yehuda-Leib Karaimsky, and I recalled how he had died, when he was brought unconscious from the synagogue[2], where between the afternoon and evening prayers he had been studying a chapter of the Mishna in the “Chabadnitse”[3]. No one thought to call a doctor. The synagogue beadle, who had brought him, just stood in the corner quietly reading psalms. Soon the gabbai of the town burial society came around too, Perez Berger, a tall Jew with a grey beard, and his assistant, a short, fat, and hairy butcher. The two of them reminded me of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (I was just reading Cervantes’s book at that time). The gabbai, acting authoritatively like a famous professor, approached the dying man, produced from his vest pocket a broken half of a small two-sided mirror, leaned over my grandfather and brought the mirror towards his nose. The mirror remained clear, not fogged, which proved that my grandfather was no longer breathing. However, as with all medical opinions, one mustn’t put faith in only one test, and to be completely sure one must perform a second one. So Berger produced from another pocket a chicken feather and placed it near his nostrils. The feather, too, did not move from its place. Now, after the second “test”, he was completely convinced in the veracity of his diagnosis and with a certain measure of pride and even satisfaction, said to his assistant: “The Jew is ours now” and closed his eyes. I was 12 years old at the time, before my bar-mitzva, but this scene is so engraved in my memory that today, after more than fifty years, the image remains before my eyes.

I continued walking closer to the fence, the place where they buried poor Jews. I found the grave of our neighbor, Hertz Kaizener, an elderly coachman who had a carriage hitched to an old mare in which he would transport passengers from Jakobstadt a distance of two kilometers to the train station in Kreutzburg. We didn’t yet have any cars in those days. All internal traffic was by horse and wagon. Carters who had good carts or worse ones (on this the price of the ride depended) were many, but passengers were few. Coachmen who would freeze in the cold in the winter all day long or roast in the burning sun in the summer offering every passerby a ride at half price, would frequently return home in the evening with empty pockets and were penniless paupers. But Hertz Kaizener had an additional misfortune. Besides being miserably poor, he was also a schlemiel. At least a few times a year, his horses would die, usually old nags who were skin-and-bones and half-blind. What could an elderly coachman possibly do without a horse? However, Jews are after all merciful people from a long line of merciful people and give much charity. They organize a committee comprising a number of important Jews, political wheeler-dealers and rich landlords in town, and seek council in how to help buy new horses for the needy coachmen. They thought it over and found an original system in Jakobstadt that I recalled as I walked here in the cemetery and passed by Kaizener’s grave. I remember, when I was 14 or 15, several times a year they would paste on the wall of the synagogue hand-written notices announcing that the in the municipal hall (a large and cold hall with a stage) on a certain night a stage play in Yiddish would be presented. No one who read the notice asked or inquired what play would be presented or who the actors would be. They asked only one question: which one of the coachmen had a horse die again? Everyone already knew the reason for the play. Our aid committee would invite from the Jewish minority theater in Riga 3 or 4 second-rate actors, recruit all the local theater-enthusiasts for the bit roles, and a few young girls and boys as extras for the dances, singing, or just to fill up the stage. I too participated a number of times in a waltz or tango on the stage, in honor of one of the new mares. Each time, they played almost the exact same material, short acts by Goldfaden or Sholem Aleichem. The greatest success was for the plays “Wandering Stars”, “The Jackpot”, and plays like that that were performed with no stage set. At best, there was a table and a few chairs on stage and always the same backdrop: a green curtain on which was painted a thick green forest of sorts and above it, in the red sky, flew a large bird that looked like a sort of a cross between a vulture and a stork. Expenditures for the play were minimal, pay only for the actors from Riga and a fee for renting the hall. All of the remaining sum was dedicated to buying a new mare. The amount left over from one showing was not always sufficient, so then a second performance was given the following evening.

We had the same Hertz Kaizener to thank for the frequent performances of the theater. When the aid committee had summoned him to hand him the money for buying the new mare, everyone always tried to influence him with words of ethics and warnings, that all this now was being done for his benefit for the last time, that he should take better care of his mare and feed her in a timely manner, because from now on he would not be given any more money, this was it. However, 5 or 6 months later, he would arrive again with downcast eyes and ask for mercy because he was once again horseless and already within a few days, a new notice would be written in ink and water-color, and the town’s Jews would once again go to watch “threater”, as my grandmother used to call it.

I also passed by the grave of the beadle of our synagogue, where my father prayed. His name was David Redlheim. He conducted great festivities in song and dance during hakafot on the holiday of simhat torah. I remember how he would line us up, children of 10 or 11, on the stage and shout at us: “Sacred lambs!”, and we would answer in chorus: “meh, meh, meh …” I also found the grave of my rabbi, the “redhead” melamed Shneiderman. There were five melameds in our town and each one had a nickname: “the new guy”, “the one who speaks twelve languages” (a young Romanian fellow who happened our way and knew many languages), and other nicknames. My melamed had a truly yellow beard and so received the unimaginative nickname, since almost nobody knew his real name. He would seat us around a table to study a page of humash or the prophets or later books of the bible, which we had to chant melodically. He himself would sit next to us and engage in other work. Slowly and very patiently, he would carve out of thin wood sticks pointers with Jewish and biblical decorations, or file out of cattle horn handles for Torah scrolls. He did this very nicely and sold his product in the synagogues of the surrounding towns and so earned himself a little something extra, since making a living solely from a melamed’s pay was very difficult. While he filed the handles, we were not afraid of him, and we allowed ourselves all sorts of mischief while studying. However, when he held a pointer 30 to 40 centimeters long in his hand that was in the final stages of being carved, the situation was completely different. He would strike with it painfully on the fingers of the five or six students until we completely lost the desire for any pranks.

This prosaic reality from the recent past, however so dear to me, that I relived on this visit to the cemetery, we buried that day together with the partially rotted bodies. Lives that were lived, ended in tragedy, exist no more, and will never be again. Not only did we bring three communities here for burial, but everything that characterized and represented Lithuanian-Latvian Jewry, its cultural, social, and religious life throughout its hundreds of years of existence and rich history.

Thus, sunken in sad thoughts, I left the orphaned, neglected cemetery where the bones of my parents and two younger brothers remained…

During the years 1943/44, as the Germans retreated from southern Russia, they took with them from the Crimean peninsula groups of Tatars that had collaborated with the German occupation authorities, so that they not fall into the hands of the Russians. The Germans didn’t want to take them to Germany, so they settled them in to most of the formerly Jewish towns in Latvia, in the small, old houses of the poorer Jews, the ones the Latvians around them didn’t want to live in. Since the Tatars are Muslims, they let them bury their dead in a corner of our abandoned cemetery. And this was for the best, at least the Tatars would not allow farmers from the area to bring their herds of cows, horses, and sheep to graze on the cemetery’s green and fat grass. Aside from that, we found there a pious Subbotnik[4], an old local Russian, who due to our and his common observance of the Sabbath, felt an affection for us and was willing to serve as a caretaker and guardian of the cemetery. We gave him free residence in the small room next to the empty cleansing room, where previously the Jewish beadle had lived, and for this he gradually brought some order into the place, he cleaned old gravestones and stood them back up and most important, guarded so that no one made off with the expensive gravestones of polished granite and marble belonging to rich Jews. A year later, we established over the large common grave a nice memorial made of granite with an inscription carved in Yiddish and Russian saying who the dead were and what towns they came from, and above it all a large Star of David.

|

This is what remains of eight hundred Jews, crates of rotted clothes and bones. In one of these twenty crates lie also the bones of my family. |

|

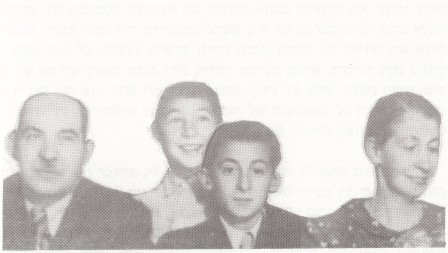

From the right: my mother Tzipporah, my younger brothers Moshe and Abba, and my father Reuven. |

|

|

|

And so this too vanishes. The bones of the three Jewish communities are covered with earth and forever only the pain in the heart and soul remain.

|

|

|

|

Nakhimovich, the cantor from Riga, signs “God full of mercy”. Around him stand the relatives of those killed, the remnants of the three communities of Jakobstadt, Viesīte, Nereta, and the other small towns in the area. |

|

The Rosenberg family brought the bones of their relatives named Rosezky, who were murdered in the neighboring town of Ungurmuiža. |

|

The procession in Kūkas on the way to the killing pits. |

One of the relatives says kaddish. |

|

|

|

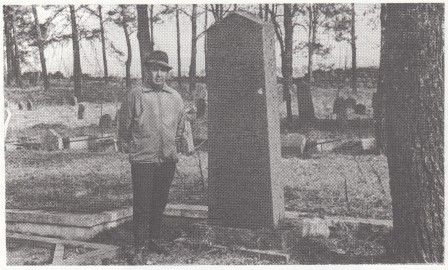

April 1971, a short time before I moved to Israel. I am standing next to the memorial in the Jakobstadt cemetery. The Star of David had disappeared from the memorial, the local party leadership or the city council ordered it to be filed off.

|

|

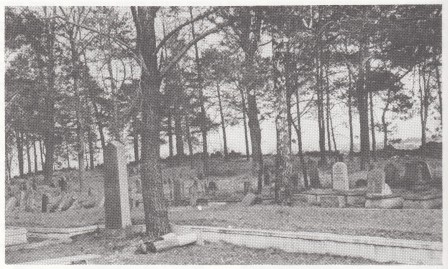

This is how the entire Jewish cemetery looked at the time, neglected and abandoned. Notes

|